Project Update: EcstasyData

Analytical Glimpses of "Molly" and Research Chemicals

December 2013

Originally published in Erowid Extracts #25

Citation: Erowid E, Erowid F. "Analytical Glimpses of "Molly" and Research Chemicals". Erowid Extracts. December 2013;25:18-19. Online edition: Erowid.org/chemicals/chemicals_testing1.shtml

Erowid's EcstasyData project started in July 2001, with the objective of identifying the contents of street ecstasy tablets. Although we have run this project for over twelve years, many Erowid visitors and members still aren't familiar with it. Samples of a drug can be anonymously submitted to a DEA-licensed laboratory for analysis (following instructions provided on EcstasyData.org), along with a payment ranging from $40 to $200. The lab analyzes each sample and sends Erowid a list of what substances were found. We publish the results on the EcstasyData website to help illuminate trends in drug distribution, substitution, and contamination as well as the specific contents of individual black-market tablets and blotter. Testing costs Erowid $160 per sample in lab and staff costs, covered in part by the co-pay and support from sponsors DanceSafe and Isomer Design.

A number of private programs and secret projects exist where individuals (who often have access to commercial or academic labs) analyze samples for friends, but few publish results of any sort. Some academic projects have purchased research chemicals and/or street products and done analyses, but it often takes a year or more between the product acquisition and publication of data. Additionally, extensive lab testing is conducted by toxicology and law enforcement labs around the world, but essentially none of their data is released to the public in a useful form.

The EcstasyData project has global importance for harm reduction and in helping promote an accurate, contempoČraneous public record of what recreational drugs are being sold. An increasingly complex world with a blizzard of new psychoactive substances demands public access to accurate identification and analysis.

Despite the term's history, it is being treated in current news reports as if it were brand new. Ignoring numerous easy-to-find web resources describing how the name "molly" is used, most news reports in September 2013 weren't able to correctly use the term.

In the mid 2000s, "molly" became more associated with the powdered/crystalline MDMA form rather than tablets and was generally used to imply purity. In the last six years, just one molly sample submitted to EcstasyData was in tablet form, and that sample contained only amitriptyline, a mildly sedating tricyclic antidepressant.

The most notable change over the last few years is the increased number of new euphoric stimulants available as pure powders. These euphoric stimulants are purchased online in bulk and then sometimes resold at the retail level as molly. Parallel to the term "ecstasy" being used for any tablet or powder that produces effects similar to MDMA, the name "molly" is now increasingly used for any euphoric stimulant in powder form.

In the last two years, EcstasyData has tested 58 samples submitted under the name "molly". Only 27 (47%) contained MDMA or MDA, sometimes in combination with other substances. Another 16 samples (28%) contained methylone, and the remaining 15 (26%) contained a variety of stimulants, including ethylone, 4-MEC, cocaine, ethcathinone, and caffeine, among others. Interestingly, none of the samples containing methylone contained any other active chemicals.

Because of the importance of both documenting what is being sold on the research chemical market and reducing harms associated with misidentified substances, EcstasyData has temporarily reduced the co-payment to $100 (down from the previous $140) for research chemical powders. This was made possible by a grant from our new sponsor, Isomer Design.

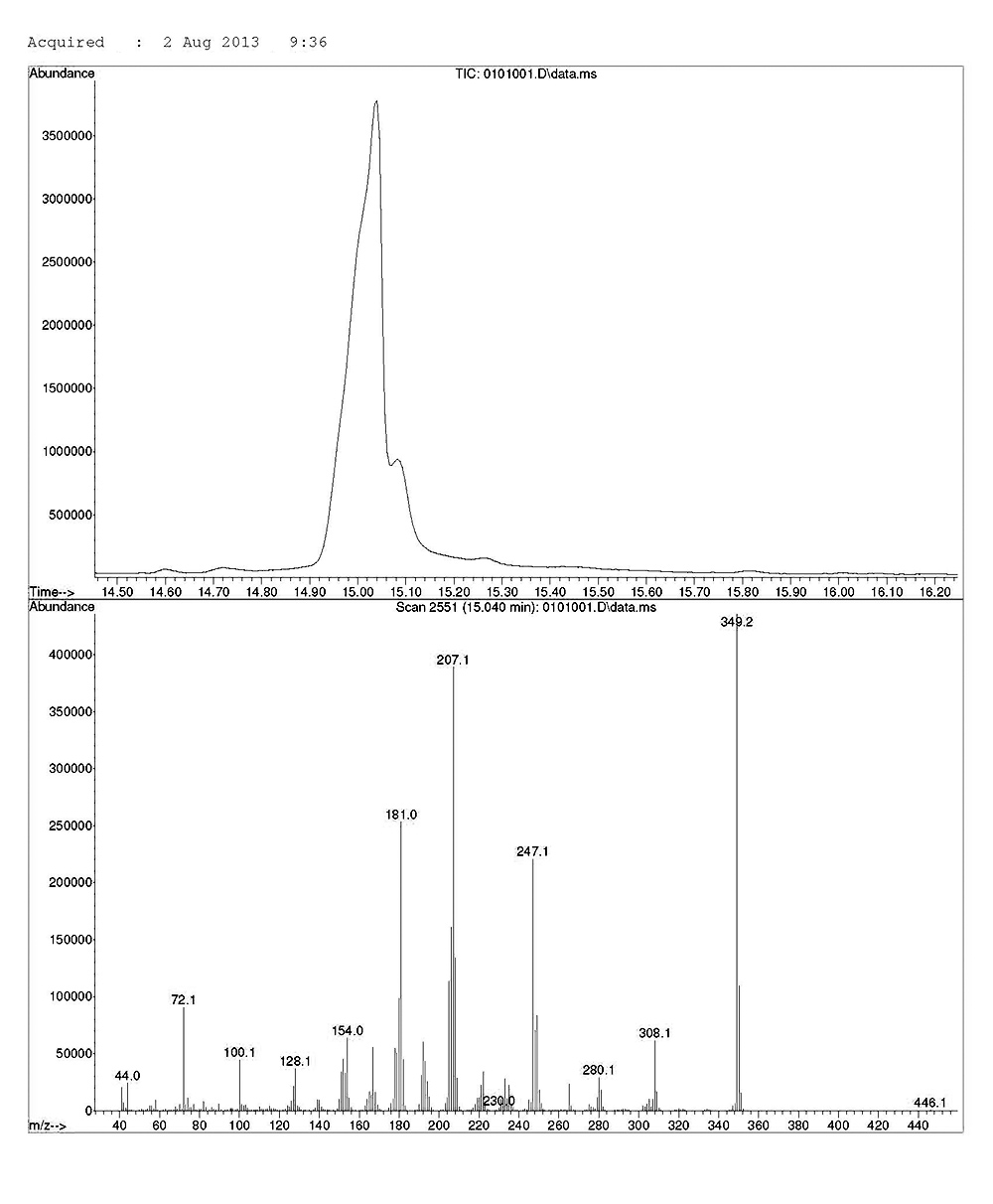

Unfortunately, the lab was unable to identify AL-LAD with gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS). Our next step was to contact analytical chemists in the Erowid Expert Network (from Canada, the UK, and Russia) who were able to confirm that the mass spectrum from the material on the blotter was correct for AL-LAD. Then, an academic lab we collaborate with tested a sample of the blotter using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). This lab took some time to sort out the extremely complex NMR results, but was able to confirm that the results were consistent with AL-LAD.

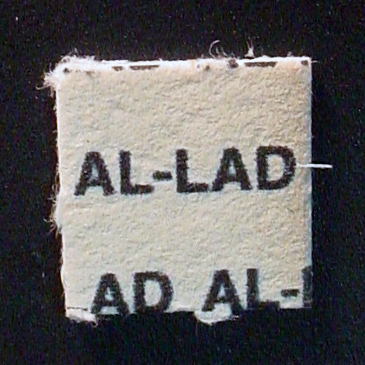

To our knowledge, this is the first published identification/analysis of commercially available AL-LAD, which has also been correlated to a number of experience reports on Bluelight and Erowid. In June, an online vendor began selling white quarter-inch square perforated blotter hits containing AL-LAD, bearing "AL-LAD" in a simple black font so it would not be resold as LSD.

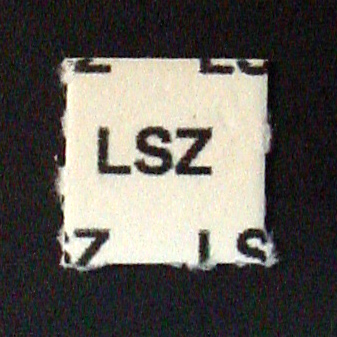

The LSZ blotter was printed in a fashion similar to the AL-LAD. With help from a number of chemists, we were able to confirm that the mass spectrum of a sample submitted to our lab was consistent with LSZ. Unfortunately, it's impossible for the GC/MS process used by our lab to identify which LSZ isomer was on the blotter, and there are three stereoisomers, only one of which is very active.

In the last two years, EcstasyData has tested 58 samples submitted under the name "molly". Only 27 (47%) contained MDMA or MDA, sometimes in combination with other substances.

Public, Open Data

EcstasyData is the only present-day project we're aware of in the world that accepts, tests, and publishes results of anonymously submitted samples of controlled substances. Other testing programs exist, but none are as open or transparent. Some European countries provide government-subsidized street drug testing, and there are a number of harm reduction groups that do on-site testing and lab analysis. But, despite more progressive regulations in many countries, none accept samples mailed by the general public, and few publish results regularly.A number of private programs and secret projects exist where individuals (who often have access to commercial or academic labs) analyze samples for friends, but few publish results of any sort. Some academic projects have purchased research chemicals and/or street products and done analyses, but it often takes a year or more between the product acquisition and publication of data. Additionally, extensive lab testing is conducted by toxicology and law enforcement labs around the world, but essentially none of their data is released to the public in a useful form.

The EcstasyData project has global importance for harm reduction and in helping promote an accurate, contempoČraneous public record of what recreational drugs are being sold. An increasingly complex world with a blizzard of new psychoactive substances demands public access to accurate identification and analysis.

Who or What is Molly?

Over Labor Day weekend (Aug 31-Sep 2), "molly" received international media attention due to several hospitalizations and deaths at festivals in the United States. "Molly" has been used as a slang name for MDMA/ecstasy for over a decade. EcstasyData's first published test result for a sample of so-called molly is from April 2000. As of December 2013, we have received 86 submitted samples identified as molly.Despite the term's history, it is being treated in current news reports as if it were brand new. Ignoring numerous easy-to-find web resources describing how the name "molly" is used, most news reports in September 2013 weren't able to correctly use the term.

|

The most notable change over the last few years is the increased number of new euphoric stimulants available as pure powders. These euphoric stimulants are purchased online in bulk and then sometimes resold at the retail level as molly. Parallel to the term "ecstasy" being used for any tablet or powder that produces effects similar to MDMA, the name "molly" is now increasingly used for any euphoric stimulant in powder form.

In the last two years, EcstasyData has tested 58 samples submitted under the name "molly". Only 27 (47%) contained MDMA or MDA, sometimes in combination with other substances. Another 16 samples (28%) contained methylone, and the remaining 15 (26%) contained a variety of stimulants, including ethylone, 4-MEC, cocaine, ethcathinone, and caffeine, among others. Interestingly, none of the samples containing methylone contained any other active chemicals.

Testing Other Drugs

Prior to 2009, nearly all samples sent in to EcstasyData's testing lab had been sold to the submitter as ecstasy. In recent years, we've increased the number of non-ecstasy samples we test. With the increase in research chemicals available for purchase online, more people are looking for verification that a chemical they purchased is what they think it is. In 2013, we've tested 80 such samples.Because of the importance of both documenting what is being sold on the research chemical market and reducing harms associated with misidentified substances, EcstasyData has temporarily reduced the co-payment to $100 (down from the previous $140) for research chemical powders. This was made possible by a grant from our new sponsor, Isomer Design.

AL-LAD

In May 2013, we were asked if we could identify AL-LAD (an uncommon, newly available ergoloid related to LSD) on blotter. The Erowid crew reported that AL-LAD had been showing up in small batches in Europe for the last month or two. After consulting with the EcstasyData lab, they accepted the sample to see if they could successfully identify its contents.

|

To our knowledge, this is the first published identification/analysis of commercially available AL-LAD, which has also been correlated to a number of experience reports on Bluelight and Erowid. In June, an online vendor began selling white quarter-inch square perforated blotter hits containing AL-LAD, bearing "AL-LAD" in a simple black font so it would not be resold as LSD.

LSZ

In June we started to hear that another synthetic ergoloid, LSZ (lysergic acid 2,4-dimethylazetidide), was circulating. A few weeks later it became available from public research chemical sales sites.The LSZ blotter was printed in a fashion similar to the AL-LAD. With help from a number of chemists, we were able to confirm that the mass spectrum of a sample submitted to our lab was consistent with LSZ. Unfortunately, it's impossible for the GC/MS process used by our lab to identify which LSZ isomer was on the blotter, and there are three stereoisomers, only one of which is very active.