“I’ve always been enthralled by insanity. ” — Julie Holland, MD

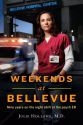

When Weekends kicks off with a bipolar fellow delivered to Bellevue naked and barking like a dog, you immediately realize that you’re in for quite a ride. Countless descriptive vignettes of Julie Holland’s patients provide readers with an intimate sense of the doctoring that she does, and how mentally trying such work can be. The book is constructed entirely from short chapters, making it a page-turner. Tucked into bed during the wee hours, I repeatedly thought, “I’ll just read one more chapter before I go to sleep…” Weekends is raw, rapid-fire, and funny.

Tales from Holland’s early days in medical school present the challenges she faced before arriving at Bellevue. Most students likely feel as if they’ve being thrown into the deep end once they are actually working in a hospital (as opposed to studying in a library) and they face having to draw blood, order medication, or check lab results for the first time. Holland does a good job conveying the insecurities that can come up when one is learning medicine, and she shares some embarrassing gaffes from her days as a student—such as not closing a speculum first before removing it during a practice exam, and causing a patient to scream curses at her when she took an arterial blood gas.

Along with the slow-down caused by inexperience, there are also the everyday fumbles in communication that hinder rapid treatment. One man insisted that he was taking “peanut butter balls” for his seizures. Considering the mental status of some of Holland’s patients, she might have simply taken him at his word, until another doctor explained that the guy was on phenobarbital. When Holland wanted to know where a patient was shot, she wasn’t really looking for the answer, “Right down on Broad Street.” Such incidents reminded me of a story my brother tells about working at NYU’s theatre department, teaching set construction to young hopefuls. One day he had to rush one of his students to the infirmary. Messing with the safety-latch on a nail gun, the kid had accidentally shot a nail through the palm of his hand. On seeing his condition, the intake nurse got a confused look on her face and asked, “Why didn’t you just stop hammering sooner?” In an emergency, it can be harder than one might think to convey the necessary details. Holland describes how her perception of humanity changed due to medical school, causing her to view everyone around her as a patient.

During her hospital work at Temple Medical School in Philadelphia, Holland realizes that she doesn’t deal well with seeing people in physical pain; she’s clearly more suited to handle psychological traumas. Her co-workers notice this too, and she frequently ends up chosen as the person to deliver bad news to a patient’s family. Between her first and second years, Holland takes a job with a psychiatrist researching auditory hallucinations, who hires her to help interview a hundred patients. While working for him in the Temple psych ward, Holland becomes enamored with Lucy, the charismatic chief resident. At first she marvels at how similar she feels they are; later, she’s surprised to learn that Lucy is a lesbian. Eventually, Holland scores a psychiatric residency at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York City, and in her third year of training she takes a two-month elective at Bellevue.

After school Holland is accepted for a schizophrenia research fellowship at Columbia. However, at the same time she gets a call from the director of the Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Program at Bellevue, where they had taken a shine to her during her elective work. He offers her a job working overnights on Saturdays and Sundays as the “weekend attending”; after some deliberation, she accepts the offer at Bellevue, where she is happy to find that Lucy is now also working. They become fast friends.

Opened in 1736, Bellevue is the oldest public hospital in the United States. Holland leads the reader through the process of admitting a patient to Bellevue, whether voluntarily or involuntarily. On arrival, Holland checks the census to see how many patients are on hold, have been admitted, or are waiting to be seen, as well as how many beds have been filled. Workers at Bellevue deal with psychotics, prisoners, the homeless, the depressed and downtrodden, and assorted addicts. (Having a schizophrenic older brother, I was touched by the insight with which Holland characterizes the problems faced by schizophrenics and their families.) In the course of seeing a patient, doctors need to determine if the person might be suicidal, needs to be put on a 24-hour hold, or can be treated and released. Descriptions of the locked detaining areas and of situations when the hospital police need to be called in provide a clear sense that the possibility of violence is ever-present; during her nine years at Bellevue, Holland faces actual harassment, as well as a physical assault.

After entering the medical profession with a hair-trigger empathy switch, Holland realizes she has had to toughen up to get her work done, and after a while she starts to feel as though she isn’t fazed by anything. Eventually she starts her own course of psychotherapy, employing the same therapist as her friend Lucy. She dives into her struggles attempting to win her father’s approval as a child, the callous manner she sometimes exhibits toward her patients, and other work-related issues that haunt her. Along with losing patients over the course of the book, she also loses a couple of friends: one to cancer, the other to suicide.

Despite the intensity of the job, and the clear need for time off to recuperate from such work, I was surprised that Holland seemed to be able to earn a living wage in New York City only working two days a week. Her light schedule eventually bites her in the ass, as the higher-ups demand that she either increase her workload or take a pay cut. Amazingly, she takes the pay cut. However, by this time she also has income from a private practice she has started, working on Fridays in a Greenwich Village office space. Doing therapy on neurotic folk with comfortable incomes starts looking a bit better than working with psychotic, economically challenged patients.

To suggest that an altered course in her professional focus was motivated by financial reasons, however, would be unfair. Dynamics at Bellevue had changed, due to shifting staff members, resulting in a less enjoyable work environment. Over the years, Holland mellows. Married, now with two kids, she starts to dislike the way in which her life has become compartmentalized. Creating a life where she has to build walls to survive feels increasingly less satisfying.

Within the psychedelic scene, Holland is known for her excellent compilation Ecstasy: The Complete Guide. Although recreational psychoactive drugs (alcohol, cocaine, heroin, PCP) mentioned in Weekends at Bellevue are usually tied to assorted unfortunate life situations surrounding her patients, there are a few positive associations included too: following a stoned conversation with Douglas Rushkoff, Holland meets her boyfriend-turned-husband at a party for Terence McKenna; she gets the chance to do some therapy on a hardened patient who comes in high on MDMA one night; she gently guides down a dude who had gotten high on mushrooms prior to visiting Alex and Allyson Grey’s Chapel of Sacred Mirrors and ultimately took to preaching in the street that folks should give away their worldly possessions.

Weekends at Bellevue is the story of a cocky young doctor transformed into a thoughtful caregiver. Through understanding her own mental foibles, Holland becomes better equipped to deal with the issues of her psych patients. People fascinated by the ways in which the mind works, and how it can go off track, will greatly enjoy reading her tale.

Fatal error: Uncaught TypeError: count(): Argument #1 ($value) must be of type Countable|array, null given in /www/library/review/review.php:699 Stack trace: #0 {main} thrown in /www/library/review/review.php on line 699