Psychoptic Reveries

Book Recommendations for Lovers of Visionary Art

Nov 2009

Citation: Hanna J. "Psychoptic Reveries: Book Recommendations for Lovers of Visionary Art". Erowid Extracts. Nov 2009;17:10-11.

The umbrella term "Visionary Art" is generally applied to works that have been inspired by an artist's inner vision. Frequently, such visions are mystical or spiritual in nature, depicting worlds or experiences that differ dramatically from material reality. Although a widely recognized subcategory is "Psychedelic Art", art that has been inspired by psychoactive substances, visionary artists may also have been inspired by transpersonal experiences, the effects of mental illness, or nonordinary states of consciousness having nothing to do with drugs. For the following reviews, I have reached beyond the works of well-known contemporary psychedelic artists and widened my scope into the larger, fuzzier realm of Visionary Art, focusing on three obscure gems.

Adolf Wölfli (1864-1930) produced his prose, poetry, musical compositions, and drawings while living as a patient at the Waldau Sanitarium, near Bern, Switzerland. Walter Morgenthaler, Wölfli's physician, produced a unique look at Wölfli in Madness & Art; it is one of the first books to focus on the art of a mentally ill person, treating him as an artist of merit, rather than viewing his work solely as a symptom of disease. Published in German in 1921, the book was translated into English by Aaron H. Esman, MD in 1992. In his introduction, Esman notes, "Above all, Wölfli and his work constitute a magnificent testimonial to the human spirit. Born and reared under the most adverse circumstances, abused and abandoned in his childhood, deprived of basic nurturance and only minimally educated, victim of a crippling mental disorder and interned for most of his adult life, he nonetheless produced a massive body of work that has fascinated artists, collectors, and scholars for three generations."

After several episodes of pedophilic behavior and a stint in prison, the court ordered 29-year-old Wölfli sent to Waldau for examination, where it was determined that he was mentally ill. Eventually diagnosed as schizophrenic, he spent the rest of his life at the institution. He suffered from intermittent hallucinations, and his violent outbursts often landed him in solitary confinement.

Most of Wölfli's work relates to inner "voyages" that he experienced until age eight. Wölfli's prose--what he considered to be an "autobiography" describing these trips--had filled 17 notebooks at the time Morgenthaler wrote his monograph.

Wölfli's drawings first attracted me to this book--they are colorful, geometric, and highly symbolic. Without doing preparatory sketching, Wölfli filled his pages from the outside inward, as though each image was perfectly formed in his head and he was simply copying it down. One remarkable display of his gift came to light when a forgotten 1904 drawing of a sun was discovered more than a decade later in a cabinet. Compared to a second drawing of the sun, done in 1919, both images contained exactly the same number of rings, bells and stars surrounding the sun, and were identically decorated with cross-hatched polyhedrons. According to Morgenthaler, Wölfli didn't have "the slightest conscious idea of the first picture!"

Morganthaler does a wonderful job of describing the symbology of the pieces without being overly psychoanalytical, occasionally speculating while maintaining a fairly conservative approach. The only things that might improve this book would be the inclusion of more art plates and a larger format, which would allow greater appreciation of the myriad small details in Wölfli's visionary works.

Characterized simultaneously as a Fantastic Realist, a Surrealist, and a Psychedelic artist, Mati Klarwein's art is difficult to pigeonhole. In 2001, about a year before he died, Klarwein sent me a copy of Improved Paintings. The works featured in this book, in their first incarnation, were purchased by Klarwein from thrift stores and flea markets, with the self-imposed restriction that none could be more expensive than a virgin canvas of equal size.

Adeptly parroting the original artists' styles, Klarwein acted as artistic savior to unwanted art, adding to the reclaimed canvases and breathing new life into them with his own unique twists. Due to his flawless technique, and because there are no "before" shots present, the viewer is placed in a joyfully ambiguous position of not being able to distinguish between "old" or "new" portions of each piece.

Peppered throughout are short commentaries from art critics, along with bits of prose and poetry that give the book a bit of a "Bob Dobbs" feel. (Indeed, there is one painting featuring the head of Bob, and the Church of the Subgenius is mentioned in Klarwein's acknowledgments.)

While the diversity of starting materials means that a wide range of styles is represented, there is still a very "Klarwein" vibe to each. Not all, nor even most, of the works could be considered beautiful, although a few are truly stunning. Considering the task that Klarwein set for himself over the 22 years that he spent on "improving" paintings, even those pieces I'd have no interest in hanging on my wall strike me as successful experiments. I always enjoy revisiting this book when I pull it down from the shelf.

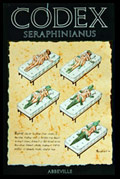

Not only is the Codex Seraphinianus my favorite book of Visionary Art, it is my favorite book, period. I recall first seeing a copy when I was 16. Despite being enthralled, I could not wrap my youthful mind around the $75 price tag. Out-of-print by the mid-1990s, a friend and I ended up finding a used copy of the 1983 American edition at Moe's for around $300. Since there was only one copy available, we decided to share it and split the cost. The book has gone in and out of print over the years, with some editions containing pages that are missing in others.

The most recent version, a 2006 Italian edition published by Rizzoli, has more pages than previous reprints, as well as a new preface. And a 2009 addition to this version is the booklet Decodex, attached to the inside back cover in a pasted-in clear plastic sleeve. Primarily in Italian, Decodex features essays and a few photos about the Codex and its creator, the Italian architect, designer, and artist Luigi Serafini.

The layout is somewhat worse in this version, with the pages enlarged and the gutter bound too tightly; also, some Codex fans feel that the print quality is a bit worse. And, while I appreciate seeing images added to this edition, their poorly chosen placement at the beginning of the book spoils the fantastic logical progression of other editions. Nevertheless, the 2006 edition is otherwise well constructed, beautiful, and more affordably priced.

So what's all the fuss about? The Codex appears to have time-travelled from some future human world or parallel dimension. It is written in an impenetrable "language", which may well be imaginary and untranslatable. Still, the more one looks at it, the more it seems to have a logical structure; the numbering system, for example, seems internally coherent. The script looks like the sort of writing that can "magically" appear in tree bark while on 2C-B. Most readers quickly abandon attempts at deciphering the text, picking up the flavor of the book from its extremely colorful and surreal illustrations. Much of this art seems straight out of the DMT realm. Flipping the pages, I recall a phrase I've often heard on the playa at Burning Man: "What am I looking at?"

The book is a natural history of a people and land both strangely similar to and disturbingly different from our own world. It moves from single-celled plant life into more complex and absurd botanicals, eventually showing their assorted uses. The viewer is taken from lower to higher forms of the animal kingdom, then through mineralogy, chemistry, and increasingly complicated technologies. Finally, what appears to be a look into the cultural anthropology, or sociology, of various geographical regions of this realm is presented. More than any other book that I own, the Codex Seraphinianus is the one I most enjoy introducing friends to.

|

Madness & Art: The Life and Works of Adolf Wölfli

by Walter Morgenthaler (1921/1992)Adolf Wölfli (1864-1930) produced his prose, poetry, musical compositions, and drawings while living as a patient at the Waldau Sanitarium, near Bern, Switzerland. Walter Morgenthaler, Wölfli's physician, produced a unique look at Wölfli in Madness & Art; it is one of the first books to focus on the art of a mentally ill person, treating him as an artist of merit, rather than viewing his work solely as a symptom of disease. Published in German in 1921, the book was translated into English by Aaron H. Esman, MD in 1992. In his introduction, Esman notes, "Above all, Wölfli and his work constitute a magnificent testimonial to the human spirit. Born and reared under the most adverse circumstances, abused and abandoned in his childhood, deprived of basic nurturance and only minimally educated, victim of a crippling mental disorder and interned for most of his adult life, he nonetheless produced a massive body of work that has fascinated artists, collectors, and scholars for three generations."

After several episodes of pedophilic behavior and a stint in prison, the court ordered 29-year-old Wölfli sent to Waldau for examination, where it was determined that he was mentally ill. Eventually diagnosed as schizophrenic, he spent the rest of his life at the institution. He suffered from intermittent hallucinations, and his violent outbursts often landed him in solitary confinement.

Most of Wölfli's work relates to inner "voyages" that he experienced until age eight. Wölfli's prose--what he considered to be an "autobiography" describing these trips--had filled 17 notebooks at the time Morgenthaler wrote his monograph.

Wölfli's drawings first attracted me to this book--they are colorful, geometric, and highly symbolic. Without doing preparatory sketching, Wölfli filled his pages from the outside inward, as though each image was perfectly formed in his head and he was simply copying it down. One remarkable display of his gift came to light when a forgotten 1904 drawing of a sun was discovered more than a decade later in a cabinet. Compared to a second drawing of the sun, done in 1919, both images contained exactly the same number of rings, bells and stars surrounding the sun, and were identically decorated with cross-hatched polyhedrons. According to Morgenthaler, Wölfli didn't have "the slightest conscious idea of the first picture!"

Morganthaler does a wonderful job of describing the symbology of the pieces without being overly psychoanalytical, occasionally speculating while maintaining a fairly conservative approach. The only things that might improve this book would be the inclusion of more art plates and a larger format, which would allow greater appreciation of the myriad small details in Wölfli's visionary works.

|

Improved Paintings

by Mati Klarwein (2000)Characterized simultaneously as a Fantastic Realist, a Surrealist, and a Psychedelic artist, Mati Klarwein's art is difficult to pigeonhole. In 2001, about a year before he died, Klarwein sent me a copy of Improved Paintings. The works featured in this book, in their first incarnation, were purchased by Klarwein from thrift stores and flea markets, with the self-imposed restriction that none could be more expensive than a virgin canvas of equal size.

Adeptly parroting the original artists' styles, Klarwein acted as artistic savior to unwanted art, adding to the reclaimed canvases and breathing new life into them with his own unique twists. Due to his flawless technique, and because there are no "before" shots present, the viewer is placed in a joyfully ambiguous position of not being able to distinguish between "old" or "new" portions of each piece.

Peppered throughout are short commentaries from art critics, along with bits of prose and poetry that give the book a bit of a "Bob Dobbs" feel. (Indeed, there is one painting featuring the head of Bob, and the Church of the Subgenius is mentioned in Klarwein's acknowledgments.)

While the diversity of starting materials means that a wide range of styles is represented, there is still a very "Klarwein" vibe to each. Not all, nor even most, of the works could be considered beautiful, although a few are truly stunning. Considering the task that Klarwein set for himself over the 22 years that he spent on "improving" paintings, even those pieces I'd have no interest in hanging on my wall strike me as successful experiments. I always enjoy revisiting this book when I pull it down from the shelf.

|

Codex Seraphinianus

by Luigi Serafini (1981, etc.)Not only is the Codex Seraphinianus my favorite book of Visionary Art, it is my favorite book, period. I recall first seeing a copy when I was 16. Despite being enthralled, I could not wrap my youthful mind around the $75 price tag. Out-of-print by the mid-1990s, a friend and I ended up finding a used copy of the 1983 American edition at Moe's for around $300. Since there was only one copy available, we decided to share it and split the cost. The book has gone in and out of print over the years, with some editions containing pages that are missing in others.

The most recent version, a 2006 Italian edition published by Rizzoli, has more pages than previous reprints, as well as a new preface. And a 2009 addition to this version is the booklet Decodex, attached to the inside back cover in a pasted-in clear plastic sleeve. Primarily in Italian, Decodex features essays and a few photos about the Codex and its creator, the Italian architect, designer, and artist Luigi Serafini.

The layout is somewhat worse in this version, with the pages enlarged and the gutter bound too tightly; also, some Codex fans feel that the print quality is a bit worse. And, while I appreciate seeing images added to this edition, their poorly chosen placement at the beginning of the book spoils the fantastic logical progression of other editions. Nevertheless, the 2006 edition is otherwise well constructed, beautiful, and more affordably priced.

So what's all the fuss about? The Codex appears to have time-travelled from some future human world or parallel dimension. It is written in an impenetrable "language", which may well be imaginary and untranslatable. Still, the more one looks at it, the more it seems to have a logical structure; the numbering system, for example, seems internally coherent. The script looks like the sort of writing that can "magically" appear in tree bark while on 2C-B. Most readers quickly abandon attempts at deciphering the text, picking up the flavor of the book from its extremely colorful and surreal illustrations. Much of this art seems straight out of the DMT realm. Flipping the pages, I recall a phrase I've often heard on the playa at Burning Man: "What am I looking at?"

The book is a natural history of a people and land both strangely similar to and disturbingly different from our own world. It moves from single-celled plant life into more complex and absurd botanicals, eventually showing their assorted uses. The viewer is taken from lower to higher forms of the animal kingdom, then through mineralogy, chemistry, and increasingly complicated technologies. Finally, what appears to be a look into the cultural anthropology, or sociology, of various geographical regions of this realm is presented. More than any other book that I own, the Codex Seraphinianus is the one I most enjoy introducing friends to.