History of Amanita muscaria

|

circa 5000-3000 BCE : The earliest evidence of Amanita muscaria use as an intoxicant is based on linguistic analysis of languages from northern Asia. Around 4000 BCE, the Uralic language split into two branches, both of which contain similar root words for inebriation. In some of these languages the root "pang" signifies both 'intoxicated' and the A. muscaria mushroom. These linguistic similarities suggest (but do not prove) that A. muscaria was known to be intoxicating before the languages split around 4000 BCE.1

|

|

500-0 BCE: Rg Veda hymns, a set of sacred stories from India, include mentions of a magical intoxicant called Soma. In 1968, R. Gordon Wasson published the controversial book Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality, speculating that Soma refers to Amanita muscaria. 100 AD: 7.5 cm high miniature statue of an Amanita muscaria dated to 100 AD found in Nayarit, Mexico, suggests A. muscaria may have been in use in coastal Mexico. Many other sculptures from Central and South America depict the ritual use of other psychoactive plants and mushrooms. circa 0 - 1800 AD: Some Scandivian historians believe that Viking 'Bezerker Warriors' ingested Amanita muscaria before going into battle. Wasson writes "No one who discusses the fly agaric in Europe can ignore the debate that has been carried on for almost two centuries in Scandinavia on this issue. First Samuel Odman in 1784 and then Frederik Christian Schubeler in 1886 propounded the thesis that those Viking warriors knows as 'beserks' ate the fly-agaric before they 'went beserk'; in short, that 'beserk-raging' was deliberately caused by the ingestion of our spotted amanita." (Soma page 341) |

|

|

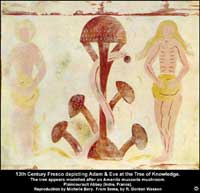

1291 AD: Fresco in Plaincourault Abbey in Indre, France depicts Adam and Eve standing beside a Tree of Knowledge which bears a striking resemblance to an Amanita muscaria mushroom. Art historians argue that this is a stylized tree having nothing to do with A. muscaria (see note) 1658 AD: Polish prisoner of war writes about a culture from western Siberia (Ob-Ugrian Ostyak of the Irtysh region) "They eat certain fungi in the shape of fly-agarics, and thus they become drunk worse than on vodka, and for them that's the very best banquet." - from Kamiensky Dluzyk "Diary of Muscovite Captivity published 1874 pg 382. 1 |

|

1730: A Swedish Colonel, Filip Johann von Strahlenberg, who spent 12 years in Siberia as a prisoner of war wrote a book titled "An Historico-Geographical Description of the North and Eastern Parts of Europe and Asia" which includes a detailed description of the practice of ingesting tea made from A. muscaria and the practice of drinking the urine of those who have ingested the mushroom in order to recycle the psychoactive ingredients."The Russians who trade with them [Koryak - a tribe on the Kamchatka peninsula], carry thither a Kind of Mushrooms, called in the Russian Tongue, Muchumor, which they exchange for Squirils, Fox, Hermin, Sable, and other Furs: Those who are rich among them, lay up large Provisions of these Mushrooms, for the Winter. When they make feast, they pour water upon some of these Mushrooms and boil them. They then drink the Liquor, which intoxicates them; The poorer Sort who cannot afford to lay in a Store of these Mushrooms, post themselves on these occasions, round the huts of the rich and watch the opportunity of the guests comind down to make water. And then hold a wooden bowl to receive the urine which they drink off greedily, as having still some virtue of the mushroom in it and by this way they also get drunk." (Wasson 1968, pg 235)1784: Samuel Odman writes a book arguing that Viking Bezerkers deliberately ingested A. muscaria to put them in a frenzy for battle. This theory is eventually accepted by many Scandinavian historians, but remains without much direct evidence to support it.Odman S Of all Swedish plants, however, I consider the Fly-Agaric, Agaricus muscarius, to be the one which really solves the mystery of the Beserks. Its use is so widespread in Northern Asia that there are hardly any nomadic tribes that do not use it in order to deprive themselves of their feelings and senses that may enjoy the animal pleasure of escaping the salutary bonds of reason... Those who use this mushroom first become merry, so that they sing, shout, etc., then it attacks the functions of the brain and they have the sensation of becoming very big and strong; the frenzy increases and is accompanied by unusual energy and convulsive movements. The sober persons in their company often have to watch them to see that they do no violence to themselves or others. The raving lasts 12 hours, more or less.Wasson and others have taken issue with this description because it seems to contradict the experiences of many who ingest the A. muscaria and find it sedating.(note) Siberian legends tell of the use of Amanita muscaria, including mentions of increased strength. (note) circa 1960-1965: A. muscaria use appears in United States urban subcultures, but remains rare because many users report the effects to be unpleasant. 1978: A Native American author, Keewaydinoquay, writes of the traditional use of A. muscaria by the Ahnishinaubeg (Ojibway) people who live near Lake Superior in North America. Although this use is assumed to be quite old, the earliest documented use is from the 20th Century. 1980s: Several books and scientific journal articles appear which describe modern and traditional use of A. muscaria as an inebriant in many areas of the world, including other native American tribes (such as the Dogrib Athabascan tribe from north west Canada), groups in Spain, and more tribes in East Asia.Ott References #

Notes #

|