Golden Guide: Hallucinogenic Plants

pages 21 to 30

.

Contents...1-10...11-20...21-30...31-40...41-50...51-60...61-70...71-80...81-90

91-100...101-110...111-120...121-130...131-140...141-150...151-156...Index

HOW HALLUCINOGENS ARE TAKEN

Hallucinogenic plants are used in a variety of ways, depending on the kind of plant material, on the active chemicals involved, on cultural practices, and on other considerations. Man, in primitive societies everywhere, has shown great ingenuity and perspicacity in bending hallucinogenic plants to his uses.

PLANTS MAY BE EATEN, either fresh or dried, as are peyote and teononacatl, or juice from the crushed leaves may be drunk, as with Salvia divinorum (in Mexico). Occasionally a plant derivative may be eaten, as with hasheesh. More frequently, a beverage may be drunk: ayahuasca, caapi, or yajé from the bark of a vine; the San Pedro cactus; jurema wine; iboga; leaves of toloache; or crushed seeds from the Mexican morning glories. Originally peculiar to New World cultures, where it was one way of using tobacco, smoking is now a widespread method of taking cannabis. Narcotics other than tobacco, such as tupa, may also be srnoked.

SNUFFING is a preferred method for using several hallucinogens - yopo, epena, sébil, rapé dos indios. Like smoking, snuffing is a New World custom. A few New World Indians have taken hallucinogens rectally - as in the case of Anadenanthera.

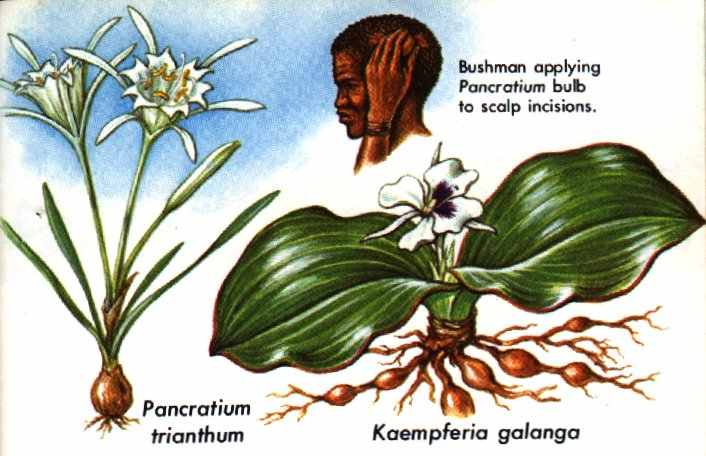

One curious method of inducing narcotic effects is the African custom of incising the scalp and rubbing the juice from the onionlike bulb of a species of Pancratium across the incisions. This method is a kind of primitive counterpart of the modern hypodermic method.

Several methods may be used in the case of some hallucinogenic plants. Virola resin, for example, is licked unchanged, is usually prepared in snuff form, is occasionally made into pellets to be eaten, and may sometimes be smoked.

PLANT ADDITIVES or admixtures to major hallucinogenic species are becoming increasingly important in research. Subsidiary plants are sometimes added to the preparation to alter, increase, or lengthen the narcotic effects of the main ingredients. Thus, in making the ayahuasca, caapi, or yajé drinks, prepared basically from Banisteriopsis caapi or B. inebrians, several additives are often thrown in: leaves of Psychotria viridis or Banisteriopsis rusbyana, which themselves contain hallucinogenic tryptamines; or Brunfelsia or Datura, both of which are hallucinogenic in their own right. (page 21)

OLD WORLD HALLUCINOGENS

Existing evidence indicates that man in the Old World --Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia--has made less use of native plants and shrubs for their hallucinogenic properties than has man in the New World.

There is little reason to believe that the vegetation of one half of the globe is poorer or richer in species with hallucinogenic properties than the other half. Why, then, should there be such disparity? Has man in the Old World simply not discovered many of the native hallucinogenic plants? Are some of them too toxic in other ways to be utilized? Or has man in the Old World been culturally less interested in narcotics? We have no real answer. But we do know that the Old World has fewer known species employed hallucinogenically than does the New World: compared with only 15 or 20 species used in the Eastern Hemisphere, the species used hallucinogenically in the Western Hemisphere number more than 100!

Yet some of the Old World hallucinogens today hold places of primacy throughout the world. Cannabis, undoubtedly the most widespread of all the hallucinogens, is perhaps the best example. The several solanaceous ingredients of medieval witches' brews--henbane, nightshade, belladonna, and mandrake--greatly influenced European philosophy, medicine, and even history for many years. Some played an extraordinarily vital religious role in the early Aryan cultures of northern India.

The role of hallucinogens in the cultural and social development of many areas of the Old World is only now being investigated. At every turn, its extent and depth are becoming more evident. But much more needs to be done in the study of hallucinogens and their uses in the Eastern Hemisphere. (page 22)

FLY AGARIC MUSHROOM, Amanita muscaria may be one of man's oldest hallucinogens. It has been suggested that perhaps its strange effects contributed to man's early ideas of deity.

Fly agaric mushrooms grow in the north temperate regions of both hemispheres. The Eurasian type has a beautiful deep orange to blood-red cap flecked with white scales. The cap of the usual North American type varies from cream to an orange-yellow. There are also chemical differences between the two, for the New World type is devoid of the strongly hallucinogenic effects of its Old World counterpart.

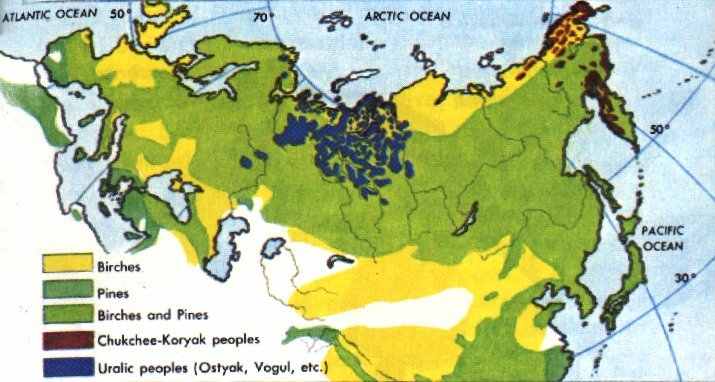

Amanita muscaria typically occurs in association with birches.The use of this mushroom as an orgiastic and shamanistic inebriant was discovered in Siberia in 1730. Subsequently, its utilization has been noted among several isolated groups of Finno-Ugrian peoples (Ostyak and Vogul) in western Siberia and three primitive tribes (Chuckchee, Koryak, and Kamchadal) in northeastern Siberia. These tribes had no other intoxicant until they learned recently of alcohol.

These Siberians ingest the mushroom alone, either sun-dried or toasted slowly over a fire, or they may take it in reindeer milk or with the juice of wild plants, such as a species of Vaccinium and a species of Epilobium. When eaten alone, the dried mushrooms are moistened in the mouth and swallowed, or the women may moisten and roll them into pellets for the men to swallow.

A very old and curious practice of these tribesmen is the ritualistic drinking of urine from men who have become intoxicated with the mushroom. The active principles pass through the body and are excreted unchanged or as still active derivatives. Consequently, a few mushrooms may inebriate many people.

A siberian Chukchee man with wooden urine vessel, about to recycle and extend intoxication from Amanita muscaria.

The nature of the intoxication varies, but one or several mushrooms induce a condition marked usually by twitching, trembling, slight convulsions, numbness of the limbs, and a feeling of ease characterized by happiness, a desire to sing and dance, colored visions, and macropsia (seeing things greatly enlarged). Violence giving way to a deep sleep may occasionally occur. Participants are sometimes overtaken by curious beliefs, such as that experienced by an ancient tribesman who insisted that he had just been born! Religious fervor often accompanies the inebriation.

Recent studies suggest that this mushroom was the mysterious God- narcotic soma of ancient India. Thousands of years ago, Aryan conquerors, who swept across India, worshiped some, drinking it in religious ceremonies. Many hymns in the Indian Rig-Veda are devoted to soma and describe the plant and its effects.

The use of soma eventually died out, and its identity has been an enigma for 2,000 years. During the past century, more than 100 plants have been suggested, but none answers the descriptions found in the many hymns. Recent ethnobotanicol detective work, leading to its identification as A. muscaria, is strengthened by the reference in the vedas to ceremonial urine drinking, since the main intoxicating constituent, muscimole (known only in this mushroom), is the sole natural hallucinogenic chemical excreted unchanged from the body.

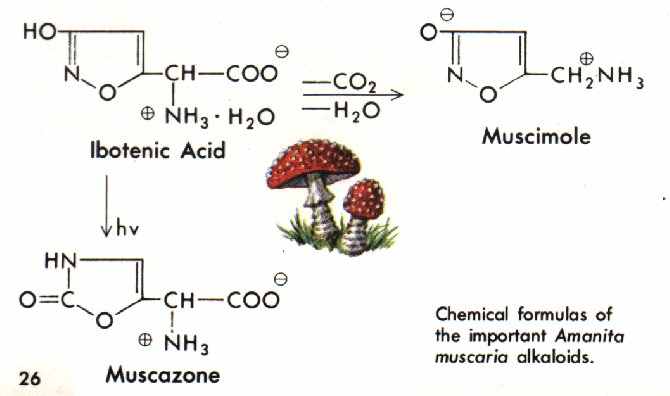

Only in the last few years, too, has the chemistry of the intoxicating principle been known. For a century, it was believed to be muscarine, but muscarine is present in such minute concentrations that it cannot act as the inebriant. It is now recognized that, in the drying or extraction of the mushrooms, ibotenic acid forms several derivatives. One of these is muscimole, the main pharmacologically active principle. Other compounds, such as muscazone, are found in lesser concentrations and may contribute to the intoxication.

Fly agaric mushroom is so called because of its age-old use in Europe as a fly killer. The mushrooms were left in an open dish. Flies attracted to and settling on them were stunned, succumbing to the insecticidal properties of the plant.

Map of Northern Eurasia shows regions of birches and pines, where Amanita muscaria typically grows, and areas inhabited by ethnic groups that use the mushroom as a hallucinogen.

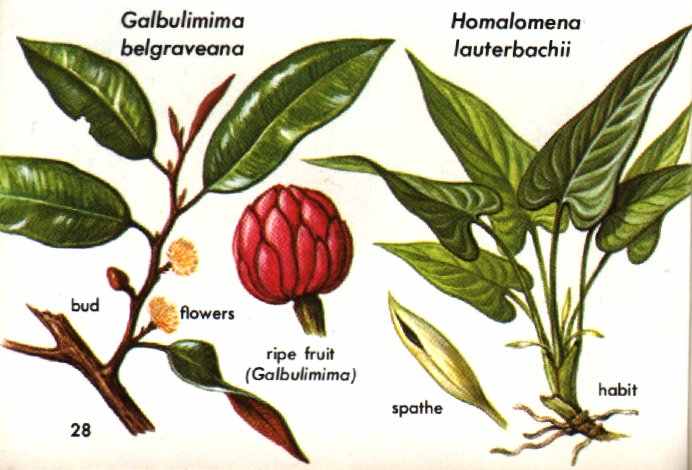

AGARA (Galbulimima Belgraveana) is a tall forest tree of Malaysia and Australia. In Papua, natives make a drink by boiling the leaves and bark with the leaves of ereriba. When they imbibe it, they become violently intoxicated, eventually falling into a deep sleep during which they experience visions and fantastic dreams. Some 28 alkaloids have been isolated from this tree, and although they are biologically active, the psychoactive principle is still unknown. Agara is one of four species of Galbulimima and belongs to the Himontandraceae, a rare family related to the magnolias.

ERERIBA, an undetermined species of Homalomena, is a stout herb reported to have narcotic effects when its leaves are taken with the leaves and bark of agara. The active chemical constituent is unknown. Ereriba is a member of the aroid fomily, Araceae. There are some 140 species of Homalomena native to tropical Asia and South America.

KWASHI (Pancratium trianthum) is considered to be psychoactive by the Bushmen in Dobe, Botswana. The bulb of this perennial is reputedly rubbed over incisions in the head to induce visual hallucinations. Nothing is known of its chemical constitution. Of the 14 other species of Pancratium, mainly of Asia and Africa, many are known to contain psychoactive principles, mostly alkaloids. Some species are potent cardiac poisons. Pancratium belongs to the amaryllis family, Amaryllidaceae.

GALANGA or MARABA (Kaempferia galanga) is an herb rich in essential oils. Natives in New Guinea eat the rhizome of the plant as an hallucinogen. It is valued locally as a condiment and, like others of the 70 species in the genus, it is used in local folk medicine to bring boils to a head and to hasten the healing of burns and wounds. It is a member of the ginger family, Zingiberoceae. Phytochemical studies have revealed no psychoactive principle.

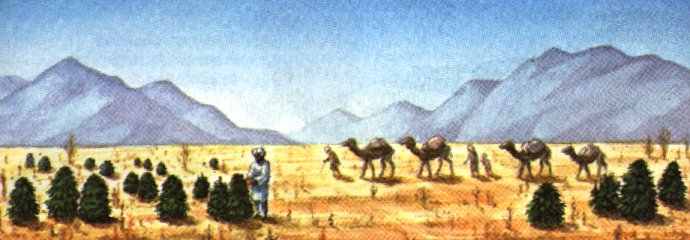

Hemp field in Afghanistan, showing partly harvested crop of the

short, conical Cannabis indica grown there.

MARIHUANA, HASHEESH, or HEMP (species of the genus Cannabis), also called Kif, Bhang, or Charas, is one of the oldest cultivated plants. It is also one of the most widely spread weeds, having escaped cultivation, appearing as an adventitious plant everywhere, except in the polar regions and the wet, forested tropics.

Cannabis is the source of hemp fiber, an edible fruit, an industrial oil, a medicine, and a narcotic. Despite its great age and its economic importance, the plant is still poorly understood, characterized more by what we do not know about it than by what we know.

Cannabis is a rank, weedy annual that is extremely variable and may attain a height of 18 feet. Flourishing best in disturbed, nitrogen-rich soils near human habitations, it has been called a "camp follower," going with man into new areas.

It is normally dioecious--that is, the male and female parts are on different plants. The male or staminate plant is usually weaker than the female or pistillate plant. Pistillate flowers grow in the leaf axils. The intoxicating constituents are normally concentrated in a resin in the developing female flowers and adjacent leaves and stems.

Contents Next